John and Joe Carlisle, Mad Management[1]

Although the Command and Control style of management is a fairly modern phenomenon, like all ideas, its roots go much further back, to a very dominant model of how to discipline and organise institutions. The philosopher Michael Foucault famously uses 18th Century Utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon as a model for how a modern disciplinary society seeks to at all times to survey, or at least give the possibility of surveillance, its populace. The panopticon is a surveillance structure originally designed by Bentham for prisons but reproducible in any environment. The centre is occupied by a watchman who cannot be seen but who is surrounded in the round by the cells or workplaces of those he surveys. Each in their own compartmentalized sections the watchman, or manager, can see everything the prisoners do. As Foucault describes ‘[t]hey are like so many cages, so many small theatres, in which each actor is alone, perfectly individualized and constantly visible.’[2]

Foucault rightly saw ‘panopticism’ as a paradigm through which individuals could be measured, assessed, marked and surveilled; it was not simply a design for a prison but a “how to” command and control for a whole variety of institutions from schools, hospitals and factories. It is worth quoting Foucault again, this time at length, as he describes the consequences of such a model:

He is seen, but he does not see; he is the object of information, never a subject in communication… if they are workers, there are no disorders, no theft, no coalitions, none of those distractions that slow down the rate of work, make it less perfect or cause accidents. The crowd, a compact mass, a locus of multiple exchanges, individualities merging together, a collective effect, is abolished and replaced by a collection of separated individualities. From the point of view of the guardian, it is replaced by a multiplicity that can be numbered and supervised.

This top down model of designing the workplace was explicitly compatible with industrialization where work was broken down into small repetitive actions that can easily be measured and codified. What is harder to understand is why the model was placed upon all forms of work. Why so many managers insist upon forcing this model onto industries, such as service, which it does not fit.

It is now common for most people who work now to have a sense of being monitored. Whether through the ubiquitous CCTV camera, which now often can record audio, to electronic clock ins,’ recordings of all phone calls made in a call centres or on workphones, targets to be hit, milometers which time how long a delivery takes to go from A to B, to IPad’s whose programs must followed to the letter. What this produces is an abundance of data, a mountain of information which can be turned into charts, graphs, and reports. This gives the manager a great sense of control; to him nothing is hidden.

Except of course a lot is hidden. Data by its very nature hides vast amounts of knowledge. The time it takes to get from A to B does not reveal that the final stage may add 20 mins because there is nowhere to park the lorry. The failure to reach the target may simply reveal the arbitrary nature of the target. In data the whole complexity of the human world is erased, flattened out into a spreadsheet, and the manager ends up mistaking the map for the terrain.

Not only does it give the illusion of knowledge but command and control management style doesn’t work. It makes waste rather than reducing it. This article will argue that it is an empirical fact that these modes of supervision fail to achieve what they claim to. Systems thinking is a far more effective way of improving organizations, and ironically, it has the data to back it up.

Systems Thinking

In 2003 Professor John Seddon published Freedom from Command and Control. [3]2 It caused quite a stir, demolishing most of the principles upon which the government had based its efficiency drive – which later morphed into wholly inappropriate and damaging austerity policies. It refuted the top down principle of leadership that is implicit in the New Public Management (NPM), which is a promoter of what Seddon calls ‘the management factory’: ‘The management factory manages inventories, scheduling, planning, reporting and so on. It sets the budgets and targets. It is a place that works with information that is abstracted from work. Because of that it can have a phenomenally negative impact on the sustainability of the enterprise.’

The case studies gave irrefutable evidence of the damage caused by this neo-liberal mechanism in the public sector. Seddon’s solution was systems thinking as expanded in his next book, Systems Thinking in the Public Sector.[4] Here example after example illustrated the waste caused by NPM, especially as advocated by the likes of Barber (targets etc.) and Varney (shared services – see appendix)

The research and analysis conducted by Professor Seddon, which has looked at reasons for diseconomies of scale specifically in service organisations, fundamentally challenges the ‘Command and Control’ logics that underpin much of the public sector. Instead case study after case study confirms that concepts such as ‘designing against demand’, ‘removing failure demand’ deliver outstanding success , while the typical drive to standardisation and specialisation of function results in inappropriate services being delivered, resulting in turn in escalating monitoring, management and correction costs.

This, however, requires a change of thinking about how organisations work best in this the 21st century. Over a hundred years ago the workforce was only one generation removed from an agricultural culture. Their understanding of industrial production and its organisation was very limited. Consequently even the best designers of organisations, e.g. Henry Ford, the Quakers, Cadburys, Rowntrees and Clarks, were at best paternal, and at worst, reductionist pragmatists, i.e. treating workers as intelligent tools. However, even the latter did not mean not trusting them or attempting to look after them. After all, Henry Ford doubled the wages of his workforce overnight and refused to allow women to labour after 5pm so they could look after their families.

Today, we have a workforce that is literate and numerate and is at home with modern organisations, BUT are managed as those of 100 years ago. Why is this? The reason is the Command and Control style is more comfortable for those leaders whose upbringing (conditioning) and training at Business Schools has brainwashed them into feeling that being in charge means taking control. As they cannot be everywhere they therefore use measuring as a proxy for their physical presence. This usually translates into columns of comparative data or run charts, tick boxes compliance, and often targets to be reached as evidence of success of failure.

So, who is the guardian in the panopticon? It is HR. In many public sector organisations HR has seized this opportunity to become the enforcer of compliance for the board. Rejoicing in their power they have abandoned their traditional role of looking after the workforce and now “guard” it.

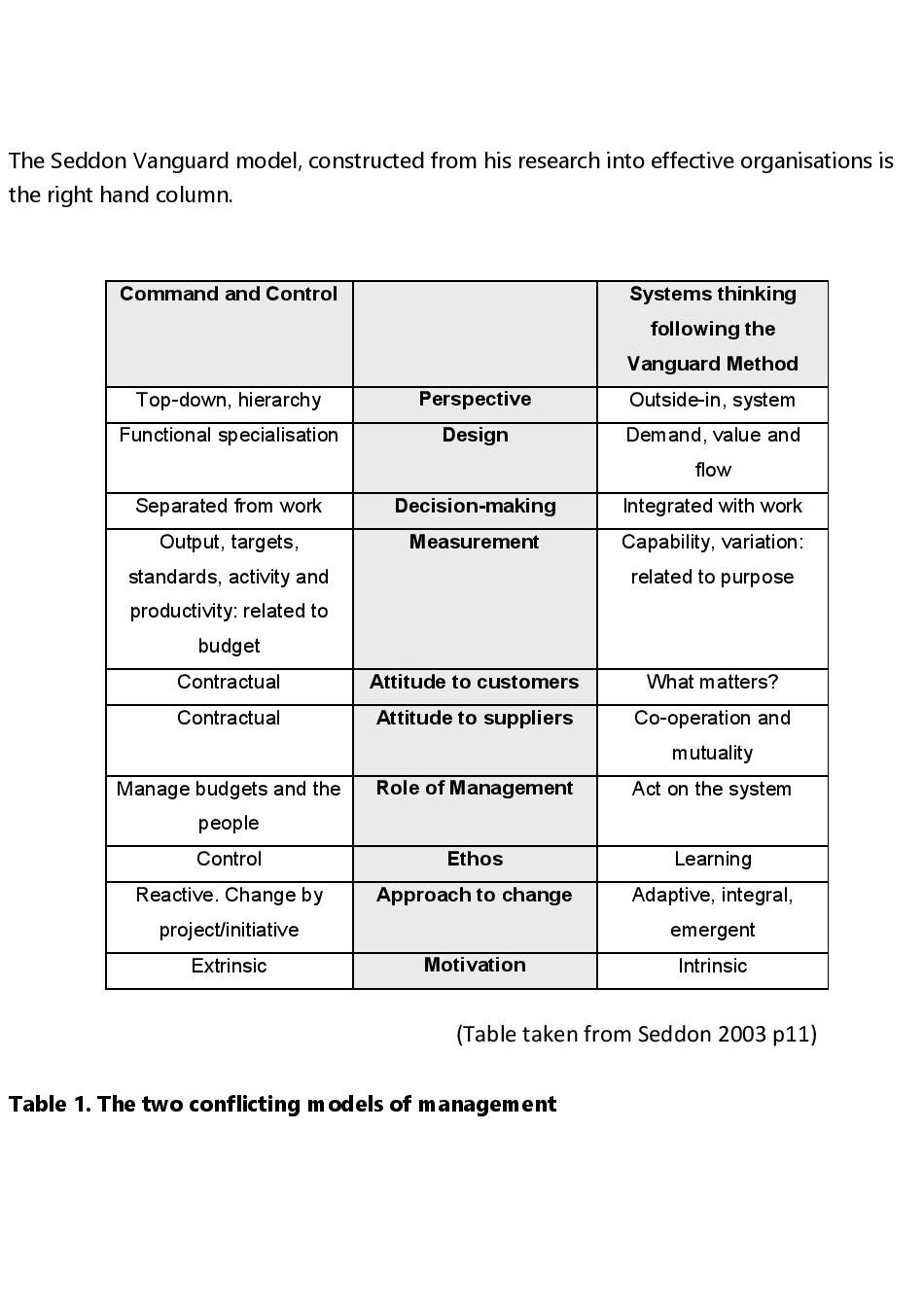

Politicians are entranced by these governance measures. They can conceive of nothing more confidence boosting than setting targets for, e.g. hospital waits, housing allocations, repairs completed. Their mental model is captured in the Table 1, below, in the left hand column. It is informed by their neo-liberal mindset, something they have imbibed from exposure to the right wing press; the fascination with material success, for example Peter Mandelson, playmaker of the Labour party said twenty years ago that he was “intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich as long as they pay their taxes”; privatisation continues even though it is clearly an utter failure; and cost-cutting and targets are the first knee jerk reactions to perceived public sector overspend.

But there is another way. It comes in the form of a System of Profound Knowledge, first propounded by the great management philosopher, Dr W. Edwards Deming, whose principles are best presented in the work of Professor Seddon, head of Vanguard. The Seddon Vanguard model, constructed from his research into effective organisations is the right hand column

Why is a bad management model sustained? The question is why, in particular do UK politicians favour the Command and Control model? My theory is that it is the “control” element that matters most – and which has caused the most waste, and this is because they are comforted by the illusion of control even when it clearly causes so much damage to people and resources as the examples in the appendix illustrate.

Dr W Edwards Deming summed it up perfectly: Most people imagine that the present style of management has always existed, and is a fixture. Actually, it is a modern invention – a prison created by the way in which people interact. He then asked the question:

“How do we achieve quality? Which of the following is the answer? Automation, new machinery, more computers, gadgets, hard work, best efforts, merit system with annual appraisal, make everybody accountable, management by objectives, management by results, rank people, rank teams, divisions, etc., reward the top performers, punish low performers, more statistical quality control, more inspection, establish an office of quality, appoint someone to be in charge of quality, incentive pay, work standards, zero defects, meet specifications, and motivate people.”[5]

Answer: None of the above. (Will someone please tell our politicians!)

All of the ideas above for achieving quality try to shift the responsibility from management. Quality is the responsibility of management. It cannot be delegated. What is needed is profound knowledge. A transformation of management is required, and to do that a transformation of thinking is required – actually the neo-liberal paradigm is so entrenched that that nothing less than metanoia (a total change of heart and mind) is needed.

Appendix

Shared Services disasters (courtesy of John Seddon submission to the Local Government and Regeneration Committee – Public Sector reform and Local Goverment. 2012)

- Western Australia’s Department of Treasury and Finance Shared Service Centre promised savings of $56 million, but incurred costs of $401 million. See http://www.erawa.com.au/cproot/9709/2/20110707%20Inquiry%20into%20the%20Benefits%20and%20CA%20with%20the%20Provision%20of%20SCS%20in%20the%20PS%20-%20Final%20Report.PDF for more details (accessed 13/2/12)

- A National Audit Office report said that the UK Research Councils project was due to be completed by December 2009 at a cost of £79 million. But, in reality, it was not completed until March 2011, at a cost of £130 million. See http://www.nao.org.uk/idoc.ashx?docId=23db711b‐66fa‐47be‐9773‐686ce60c0218&version=‐1 (accessed 13/2/12)

- The Department for Transport’s Shared Services, initially forecast to save £57m, is now estimated to cost the taxpayer £170m, a failure in management that the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee described as a display of ‘stupendous incompetence’. The most recent evidence of the higher cost was documented in a House of Commons Transport Select Committee report (http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmselect/cmtran/549/549.pdf accessed 13/2/12)

[1]https://jcashbyblog.wordpress.com

[2]Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish, trans. A. Sheridan (Vintage books, New York, 1995) p. 200

[3] Seddon 2003 ‘Freedom from Command and Control’ Vanguard Education

[4] Seddon 2008 ‘Systems thinking in the Public Sector’ Triarchy: Axminster

[5] Deming, W.E. (1993) Out of the Crisis MIT: Cambridge